Wearing a smartwatch should make you healthier—not expose you to “forever chemicals.” In this post, I’ll unpack what recent findings suggest about PFAS in smartwatch bands, why it matters for your health, and the smartest ways to lower exposure for you and your family.

What Are PFAS—and Why Are They in Wearables?

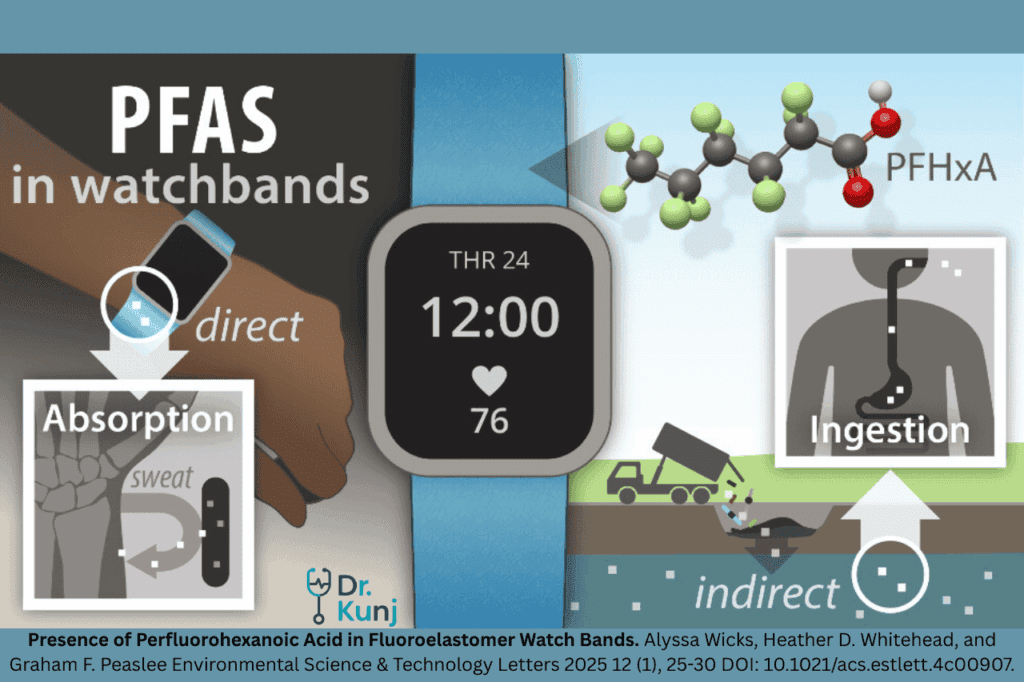

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are a large family of water- and oil-repellent chemicals used in everything from nonstick cookware to stain-resistant fabrics. They don’t easily break down in the environment or the body—hence the nickname “forever chemicals.” Manufacturers may use them to make bands comfortable, “sweatproof,” and durable.

The Study Signal You Shouldn’t Ignore

A recent analysis of smartwatch bands reported hazardous levels of PFAS in most samples—15 out of 22 (68%) tested bands contained concerning concentrations. Notably, it wasn’t just budget accessories; mid-tier and premium bands were among the most likely to contain these compounds. If you wear your device during workouts (when you sweat and your pores open), your absorption risk can increase.

The Health Concerns Linked to PFAS

While research is ongoing, PFAS exposure has been associated with a range of conditions:

- Cardiometabolic: arrhythmias, hypertension, high cholesterol, heart disease.

- Skeletal: osteoporosis.

- Immune: immune suppression (impaired vaccine response has been reported in some contexts).

- Oncologic: higher risk of kidney and testicular cancer in some exposed populations.

No single wristband is a diagnosis, and association ≠ causation. But the signal is strong enough—and the exposure so widespread—that minimizing your burden is a prudent move.

Should You Test Your PFAS Levels?

You can measure PFAS through commercial labs (e.g., large diagnostic networks) or reliable at-home kits. Testing is useful if:

- You’ve had known high exposures (e.g., firefighting foams, contaminated water supplies).

- You need a baseline to assess the effect of your exposure-reduction efforts.

- You’re considering blood or plasma donation strategies (more on that below).

If you’re not going to act on the result, testing may add cost without benefit. Either set a plan to reduce exposure regardless or use testing to guide and verify your plan.

The Most Effective Ways to Reduce PFAS Exposure

H2O: Filter First

- Reverse osmosis (RO) and activated carbon (charcoal) filters can meaningfully lower PFAS in drinking water.

- If possible, filter the main kitchen tap (and any tap used for infant formula). Replace filters on schedule—saturated filters don’t help.

Diet: Bind and Eliminate

- High-fiber foods (vegetables, legumes, whole grains, chia, flax) can bind toxins in the gut and support elimination.

- Aim for 25–38 g/day of fiber (adults), adjusting gradually to avoid GI upset.

Cookware: Ditch Nonstick, Go Durable

- Reduce PFAS exposure by avoiding nonstick pans when possible.

- Choose stainless steel or cast iron—they’re long-lasting, naturally non-toxic, and oven-safe. Think: Be an iron person, not a PFAS person.

Lifestyle: Support Detox Pathways

- Don’t smoke, and limit alcohol—both increase oxidative stress and can compound toxin burdens.

- Sleep 7–9 hours nightly; deep sleep supports immune balance and repair.

Emerging Interventions: What the Research Suggests

Blood and Plasma Donation

A randomized study in firefighters—an occupation with higher PFAS exposure—found that regular blood or plasma donations (every 6–12 weeks) reduced circulating PFAS levels, with plasma donation showing an even greater effect. This isn’t a household fix for everyone, but it’s a promising, real-world strategy you can discuss with your clinician, especially if your levels are elevated and you’re otherwise eligible to donate.

Plasmapheresis Technology

In vitro work (lab testing of the plasmapheresis tech itself) demonstrates that PFAS can be removed rapidly from plasma in a controlled setup—up to ~90% within 60 minutes and nearly complete within two hours. While this is not yet a standard clinical therapy for PFAS, it signals where medical treatments may be headed.

Bottom line: Donation has evidence for modest, real-world reductions; advanced filtration and apheresis are emerging and may inform future care.

Smartwatch Safety: Practical Steps You Can Take Today

1) Swap Your Band

If you love your device, change the strap. Favor materials less likely to contain PFAS and that limit prolonged skin contact:

- Metal bands (e.g., stainless steel, titanium)

- Textiles like cotton or linen (note: not sweat/water-proof)

- Leather (from reputable sources, mindful of other finishes)

Rotate bands and clean your wrist after workouts. If you notice irritation, remove the band, wash the area, and consider switching materials.

2) Rethink Workout Habits

- During intense exercise when sweating and vasodilation increase absorption, try a clip-on or pocket carry for activity tracking, especially if you suspect your band contains problematic materials.

- Rinse and dry the band post-workout; sweat residue can carry contaminants.

3) Audit Your Other PFAS Sources

- Food packaging: reduce contact with grease-resistant wrappers (often PFAS-treated).

- Stain-resistant sprays/fabrics: avoid when you can.

- Cosmetics and ski waxes: look for PFAS-free labels and third-party certifications.

A Simple, Science-Backed Action Plan

Week 1: Immediate Wins

- Install or verify your RO or activated carbon water filter.

- Replace your smartwatch band with metal or natural fabric.

- Swap one nonstick pan for stainless steel or cast iron you’ll use daily.

Week 2–4: Build Momentum

- Increase dietary fiber by 5–10 g/day (add legumes, leafy greens, berries, chia).

- Set a sleep schedule (consistent bedtime/wake time, dark cool room).

- If curious, schedule a baseline PFAS test.

Month 2–3: Verify and Optimize

- If you donate blood/plasma and are eligible, consider regular donations (discuss with your clinician).

Retest PFAS in 3–6 months if you need objective feedback on your plan.

Key Takeaways (TL;DR)

- PFAS (“forever chemicals”) are turning up in many smartwatch bands, including higher-priced models.

- Because you wear bands while sweating, skin absorption risk may rise during exercise.

- Practical steps work: water filtration (RO/activated carbon), high-fiber diet, stainless/cast-iron cookware, better sleep, and avoiding tobacco/alcohol.

- Blood or plasma donation can lower PFAS levels in eligible donors; plasmapheresis is a promising technology still evolving.

- Swap your band to metal, cotton, or linen, and clean your wrist after workouts.

For a concise walkthrough with visuals and examples, dive into the video: PFAS in smartwatches.

Disclaimer: This article is educational and not a substitute for personal medical advice. If you have symptoms or elevated test results, consult your healthcare professional.